Researchers have uncovered a surprising connection between pain and viral infections that doesn’t involve inflammation. A recent study shows that a specific immune sensor called STING can trigger pain by activating certain neurons in the body, all without causing inflammation. This discovery could lead to new treatments for viral-related pain, like the pain caused by herpes or even COVID-19.

Let’s explore how this finding could change the way we treat pain caused by viral infections and why it matters for future medical treatments.

Understanding the Role of STING in Pain

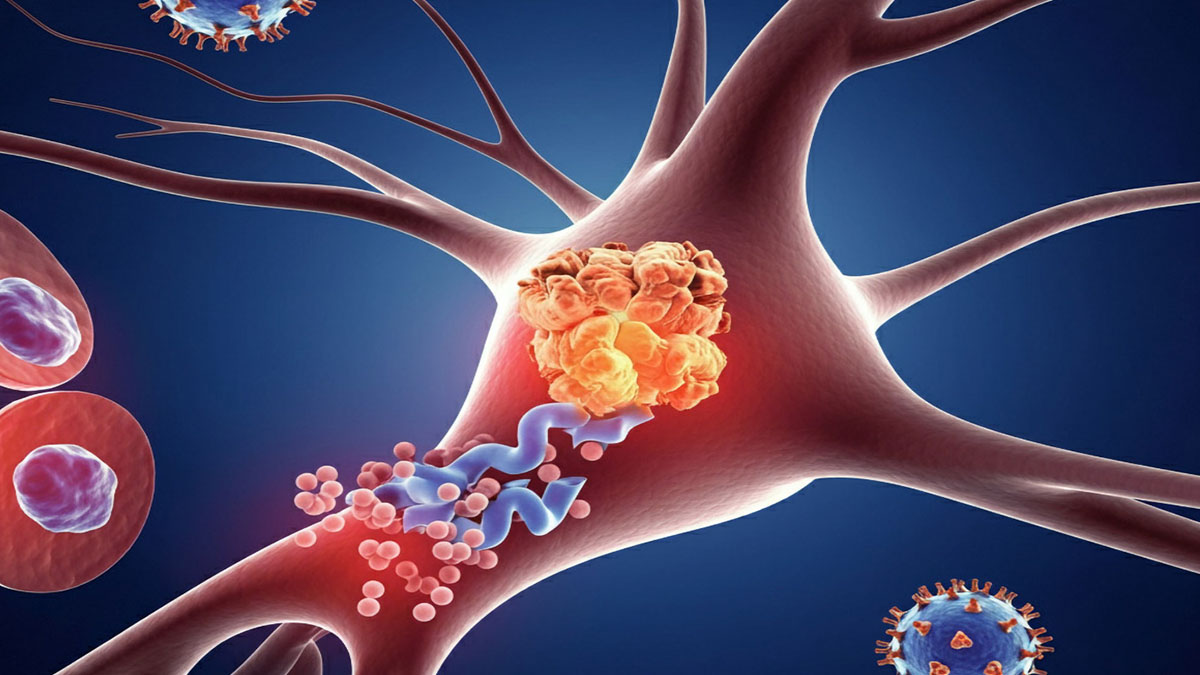

STING (Stimulator of Interferon Genes) is an important part of the body’s innate immune system, which helps detect viral infections. While STING was originally known for its role in triggering the immune response, scientists now realize that it also plays a direct role in causing pain.

Key Findings of the Study:

- STING can trigger pain receptors (nociceptors) without causing inflammation.

- Pain is induced by viral fragments, like DNA, that activate STING.

- Blocking STING activity in mice significantly reduced pain, even though inflammation and viral load remained unchanged.

How Viruses Trigger Pain Without Inflammation

Pain is often one of the first signs of an infection. Traditionally, pain has been thought to occur as a result of inflammation, the body’s immune response to an invading virus or bacteria. However, this study reveals that viral infections can cause pain through a different pathway one that doesn’t require inflammation.

The researchers discovered that STING, when activated by viral DNA, directly affects pain-sensing neurons known as nociceptors. This activation happens through a specific ion channel called TRPV1, which causes the neurons to send pain signals to the brain.

Key Mechanisms Behind Viral Pain:

- STING activation: Viral DNA activates STING in nerve cells.

- TRPV1 ion channel: Once STING is activated, it opens the TRPV1 channel, which is responsible for pain perception.

- Neuron depolarization: This process leads to the activation of pain-related neurons, causing the sensation of pain.

Insights from the Herpes Virus

The study mainly focused on mice infected with herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1), which is closely related to the virus that causes chickenpox and shingles. When STING was removed from the nociceptors of these mice, the amount of pain they experienced was significantly reduced. This suggests that STING is directly responsible for viral-related pain.

Why This Matters for Other Viral Infections

The discovery of this STING pathway is exciting because it could apply to a wide range of viral infections, including COVID-19. Research is already underway to see how SARS-CoV-2, the virus responsible for COVID-19, interacts with STING and whether this could explain some of the pain symptoms seen in people with the virus.

Other Viruses That May Cause Pain via STING:

- Herpes simplex virus (HSV)

- Varicella-zoster virus (VZV), which causes shingles

- SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19)

Potential for New Pain Treatments

The discovery that STING is involved in viral pain pathways opens the door to new pain relief treatments. Current pain relief methods often focus on reducing inflammation, but this study shows that it may be possible to block pain without affecting the immune system. This is particularly important during viral infections when maintaining a healthy immune response is crucial.

Why This Discovery is Important for Pain Management:

- Targeting pain directly: By blocking STING, doctors could potentially reduce pain without interfering with the immune system.

- Better treatments for viral infections: New pain treatments could be developed that don’t rely on anti-inflammatory drugs, making them safer for long-term use.

- Improved quality of life: For people who suffer from chronic pain due to viral infections, such as shingles or COVID-19, this discovery could offer relief without the need for strong painkillers or anti-inflammatory medications.

Ongoing Research and Future Implications

The researchers, from Brazil, the United States, and South Korea, believe that this discovery could lead to breakthroughs in treating pain from viral infections. The next steps involve understanding how this mechanism might work in other types of infections, such as bacterial or fungal infections.

Dr. Thiago Mattar Cunha, one of the study’s authors, explained that this new concept could change how we think about pain management, particularly in relation to infections. He believes that focusing on this STING pathway could lead to therapeutic strategies that relieve pain without compromising the immune system.

The Impact of Chickenpox and Shingles

The research group also explored how viruses like varicella-zoster virus (VZV), which causes chickenpox and shingles, affect pain. Although chickenpox is usually mild in children, the virus can remain in the body for years and reemerge later in life as shingles. Shingles often causes severe pain known as herpetic neuralgia.

The discovery of the STING pathway could lead to better treatments for the chronic pain experienced by people with shingles or other herpes-related infections.

Facts About Chickenpox and Shingles:

- Chickenpox is a common viral infection that causes an itchy, blistering rash.

- Shingles is a reactivation of the varicella-zoster virus that causes painful skin lesions.

- Shingles pain, or herpetic neuralgia, can be long-lasting and difficult to treat.

Conclusion: A New Approach to Pain Relief

The discovery of the role of STING in viral pain offers hope for new non-inflammatory pain treatments. By targeting this specific immune sensor, doctors may be able to relieve pain without affecting the body’s ability to fight off infections. This breakthrough could change the way we treat pain during viral infections, providing relief to millions of people who suffer from pain caused by conditions like shingles, herpes, or even COVID-19.

References:

Lee, S.H., et al. (2024). STING recognition of viral dsDNA by nociceptors mediates pain in mice. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbi.2024.07.013

Editor’s Note: This article is a reprint. It was originally published here: Health News