September 26, 2018

Michael Joyce is a writer-producer with HealthNewsReview.org and tweets as @mlmjoyce

Including “exercise” and “Alzheimer’s” in the same headline is sure-fire clickbait for a lot of people. For example:

150 minutes of exercise every week can reduce risk of Alzheimer’s disease (The Economic Times)

Exercise may delay rare form of Alzheimer’s (HealthDay)

But these headlines refer to a study published earlier this week that doesn’t justify such strongly suggestive wording. Here’s why.

The study

The researchers evaluated 275 people with “autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s disease” (ADAD), an inherited form of the disorder that represents less than 1% of all Alzheimer’s, and most often leads to symptoms of dementia by age 50. They wanted to see if exercising more than 150 minutes each week was associated with differences on cognitive/functional tests, as well as biomarkers in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) surrounding the brain of patients with ADAD.

They found that, when compared to those with low physical activity (‘PA’ < 150 minutes/week), the high PA group (>150 minutes/week) performed slightly better on cognitive tests, and showed a drop in the tau protein biomarker associated with Alzheimer’s.

Researchers used a hypothetical, mathematical model — based on the onset of dementia in first-degree relatives with the disorder — to estimate when they thought those with ADAD would develop signs of dementia, and found that those who exercised more showed signs of “very mild dementia” earlier than expected.

The limitations

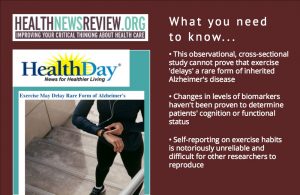

But there are several key limitations of this “observational, cross-sectional” study design that may limit just how clinically relevant these findings really are.

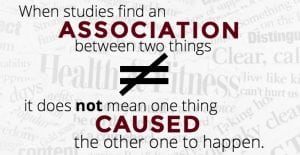

First, as we have written about before, this study cannot tease apart which way causality (if any) runs: Does exercise actually protect against dementia? Or do those who have dementia exercise less?

First, as we have written about before, this study cannot tease apart which way causality (if any) runs: Does exercise actually protect against dementia? Or do those who have dementia exercise less?

Second, a cross-sectional study examines a single point in time. That means for a progressive disease like Alzheimer’s, making projections about delaying or slowing the disease — as both news stories above suggest — is hypothetical and not proven by the study’s findings.

Third, changes in levels of biomarkers associated with Alzheimer’s disease (like tau or beta-amyloid) have not been proven to determine patients’ cognition or functional status. [Read more about surrogate markers in Alzheimer’s research here.]

Also, the touted benefits of exercise are based on cognitive test results that — although statistically significant — are incomplete measures of cognition and functional status and don’t necessarily translate to “thwarted mental decline” as claimed in the HealthDay article.

Finally, researchers relied upon subjects self-reporting their type and estimated duration of exercise, but not the intensity. This is both unreliable and hard to reproduce.

The take-home message

Just because this study cannot prove cause-and-effect doesn’t make it a ‘bad’ study. But longer-term, randomized controlled studies are needed before clear links between exercise and dementia can be established.

Just because this study cannot prove cause-and-effect doesn’t make it a ‘bad’ study. But longer-term, randomized controlled studies are needed before clear links between exercise and dementia can be established.

“There’s quite a body of work building up now that shows beneficial effects of exercise on cognition,” said Susan Molchan, MD, a psychiatrist and former NIH clinical researcher who studied Alzheimer’s disease.

“There’ve been a few randomized controlled trials, though the results are not completely consistent. Not all of them have shown a benefit but, then again, none of them have shown a risk. I’m glad to see non-drug interventions being explored. And it doesn’t hurt to exercise as long as you do it safely and within your own limits.”

In other words, there are plenty of evidence-based reasons to get over 150 minutes of aerobic exercise every week. But, at this time, “thwarting” Alzheimer’s isn’t one of them.