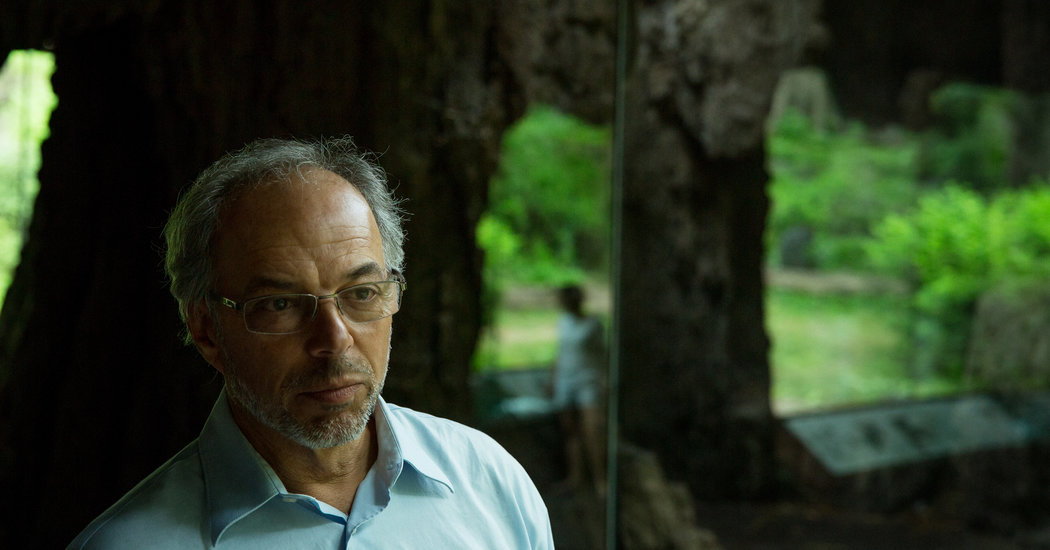

Carl Safina, 64, an ecologist at Stony Brook University on Long Island and a “MacArthur genius” grant winner, has written nine books about the human connection to the animal world. Coming next spring is “Becoming Wild,” on the culture of animals, and a young adult version of “Beyond Words,” on the capabilities of dogs and wolves.

We spoke over lunch in his Long Island garden, surrounded by his three dogs, some wild squirrels and a group of extremely tame hens. An edited and condensed version of our conversation follows.

When a writer for the Sierra Club’s magazine recently put the words “animal” and “cognition” into Google Scholar, he was directed to almost 200,000 citations published in the past five years. Why the explosion of interest in this scientific area?

I think it’s happened because in recent years we’ve come to know much more about the inner activity of nonhuman minds.

We have tools today that didn’t exist 50 or even 10 years ago. There are researchers putting dogs into M.R.I.’s, and so it’s become possible to watch their brains do things. What we’re learning is that animals do have felt experiences and thus, I think, consciousness.

What’s your definition of consciousness?

To me, consciousness is the thing that feels like something. It’s the sensation of experiencing the input from your sense organs. We’re learning that a lot of animals — dogs, elephants, other primates — have it.

How else has research on animal behavior improved?

Well, until the 1950s and the 1960s, the study of animal behavior wasn’t seen as real science. Until Jane Goodall, Iain Douglas-Hamilton and George Schaller began publishing, there were few studies. They were among the first to watch wild animals for the purpose of describing their behavior. Before, if you wanted to study elephants, you shot them and pulled their molars out to see how old they were.

Thanks to these pioneers, we’ve learned that wild animals do complicated things. Many recognize the individuals around them — even solitary animals, like mountain lions. There usually is a male mountain lion with a large territory who visits a few females inhabiting the territory. The females all know each other. The adjacent males know who their neighbors are.

Who knew that dolphins could recognize each other after a long separation? Yet, scientists report that there was a dolphin in an aquarium who hadn’t seen another captive dolphin in 20 years. When they were reunited, there was immediate recognition.

Frans de Waal’s latest book, “Mama’s Last Hug,” chronicles the emotional deathbed reunion of an aged zoo chimpanzee and primatologist Jan van Hooff, who had worked with her for many years. Though Mama is listless, when Dr. van Hooff approaches her after a long separation, she recognizes him and reaches out to touch him.

Chimpanzees, dolphins, elephants — they’ve all demonstrated signs of recognizing individuals. Videos show that their recognition is not mechanical, not a chemical match with a stored memory bank. It is often accompanied by shows of emotion, which proves to me that the experience is felt.

Has the internet widened our understanding of the animal world?

I’d say so. Almost everyone nowadays has a video camera on them all the time, and animal behaviors get recorded that we haven’t seen before. The other day, someone sent me a video where someone was backing up their car and a puppy went behind it. Another dog came streaking out at high speed, snatching the puppy away.

Thanks to the ubiquity of these videos, we’re seeing evidence that the envelope of what animals can do is much bigger than we thought. That leads me to wonder: why, despite increasing evidence, do some people deny that animals have emotions or feel pain?

What’s your guess?

I think it’s because it’s easier to hurt them if you think of them as dumb brutes. Not long ago, I was on a boat with some nice people who spear swordfish for a living. They sneak up to swordfish sleeping near the surface of the water and harpoon them, and then the fish just go crazy and kind of explode. When I asked, “Do the fish feel pain?,” the answer was, “They don’t feel anything.”

Now, it’s been proven experimentally that fish feel pain. I think they feel, at least panic. They clearly are not having a good time when they are hooked. But if you think of yourself as a good person, you don’t want to believe you’re causing suffering. It’s easier to believe that there’s no pain.

As a child, did you have pets?

I did. I spent my first 10 years in Brooklyn, where I had the kind of pets you’d buy in a store — a parakeet, little turtles.

From the time I was 7, I had homing pigeons. I learned about life, with a capital “L,” from them. The pigeons figured out who they were going to mate with. They’d be out flying around during the day and they’d come home, feed their babies and go to sleep. Watching them go about their lives, you saw them do a lot of the things that humans do. It was there right in front of your eyes.

Then, I went to college and I learned that my childhood observations were not allowed. They were “anthropomorphic.” But the more I see of the new neuroscience and neurochemistry, I see a lot of overlap. All of life is literally kin. I first learned that from my Brooklyn pigeons.

You live with three dogs. What have you learned from them?

Among things, that they are capable of anticipation. For instance, they show much excitement when I simply touch my car keys, which might well signal that they are going to some place interesting, like the beach. That proves that they have imagination and even memory.

Another thing — and this shouldn’t surprise — they can be quite emotional. Some years ago, I lived with someone with a dog. Before we broke up, we argued a lot. Once, we took her dog to the beach and we started bickering there. That dog just basically collapsed into a pile of leaves and would not get up. She did not want to be with us! And we weren’t even yelling at her. She just did not want to be a part of an unhappy scene.

That showed me that they can have a real-time valuation of their experiences. They know what they prefer to avoid.

The psychologist who puts dogs into M.R.I.’s, Dr. Gregory Berns, wrote a book in 2013 titled “How Dogs Love Us.” Do you think your dogs do?

That’s easy. Yes! And I don’t need to scan their brain activity to know this. They show it in their actions and the choices they make. Our dogs sleep on the floor in our bedroom just to be near us.

We’ve never given them any treats in that room. The only thing they get for the effort of climbing the stairs is proximity to us. At dawn, two of the three jump on the bed. Jude, the third, has a knee problem, and he can’t. When we wake up, it’s always all tongues and tails and, “Oh happy day!”

During the day, they roam free in the house and the yard. If I’m writing or working outside, they’re never more than a hundred feet from me. That’s their choice.

My point is that they seek us out just to be near us. And what is love’s fundamental emotion? It’s the desire to be near loved ones. So yes, dogs can love their humans.