Reports from thousands of women that breast implants are causing problems like debilitating joint pain and fatigue, claims long dismissed by the medical profession, are receiving new attention from the Food and Drug Administration and researchers.

This may be a long-awaited moment of validation for tens of thousands of women who have been brushed off as neurotic, looking to cash in on lawsuits or just victims of chance who coincidentally became ill while having implants.

The F.D.A. has begun to re-examine questions about implant safety that have long been disputed by doctors and implant manufacturers, and that most consumers thought had been resolved a decade or so ago.

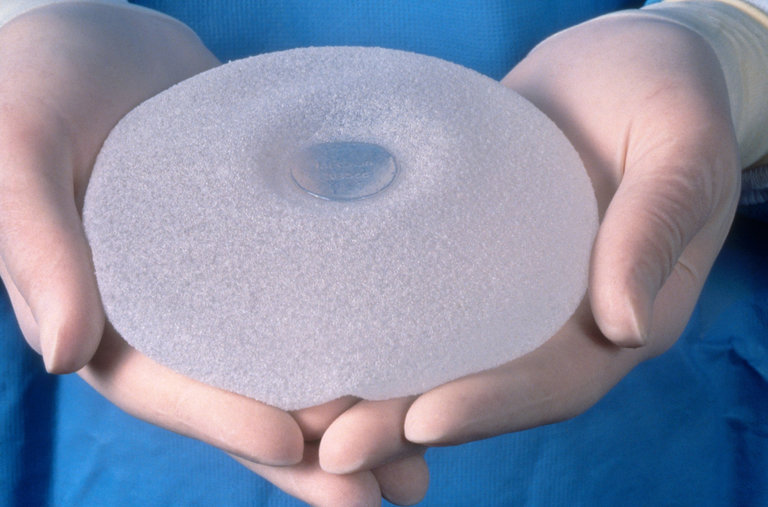

Millions of women have implants, which are silicone sacs filled with either salt water or silicone gel, used to enlarge the breasts cosmetically or to rebuild them after a mastectomy for breast cancer.

[Like the Science Times page on Facebook. | Sign up for the Science Times newsletter.]

On Tuesday, the agency warned two makers of breast implants that they had failed to conduct adequate long-term studies of the devices’ effects on women’s health. Those studies were mandated as a condition of approving the implants, and the agency cautioned that the devices could be taken off the market if the research wasn’t properly carried out.

The agency also issued a statement on Friday that applied to a broad array of medical devices, acknowledging that implanted devices may make some people sick. “A growing body of evidence suggests that a small number of patients may have biological responses to certain types of materials in implantable or insertable devices,” the agency said. Those effects can include “inflammatory reactions and tissue changes causing pain and other symptoms that may interfere with their quality of life.”

The F.D.A. said it was gathering information to fill information gaps in the science “to further our understanding of medical device materials and improve the safety of devices for patients.” Silicone, used in implants, is one of the materials under scrutiny.

And next week, the agency will hold a two-day meeting about breast implants, hearing from researchers, patient advocacy groups and manufacturers.

One problem to be discussed is an uncommon cancer of the immune system called anaplastic large cell lymphoma, which has been detected so far in 457 women with breast implants, according to the F.D.A. Removing the implants usually eliminates the disease, but some women have also needed chemotherapy, and 17 deaths from the cancer have been reported worldwide.

Nearly all the lymphoma cases have occurred in women who had implants with a textured surface, rather than a smooth one. Textured implants made by Allergan, a major manufacturer, were taken off the market in Europe in December. Smooth implants are used more often than textured ones in the United States.

Another focus of the conference will be “breast implant illness,” which encompasses disorders that may involve the immune system and can cause muscle pain, fatigue, weakness, cognitive difficulties and other debilitating symptoms. Some ailments fall into a category called connective tissue disease, which includes lupus, rheumatoid arthritis and other serious autoimmune diseases.

The F.D.A. website says the agency “has not detected any association between silicone gel-filled breast implants and connective tissue disease.” But it adds, “In order to rule out these and other complications, studies would need to be larger and longer than these conducted so far.”

The new warnings are of potential concern to millions of women with implants. About 400,000 women in the United States get breast implants every year, including 300,000 for cosmetic reasons and 100,000 for reconstruction after mastectomies performed to treat or prevent breast cancer. Worldwide, about 10 million women have breast implants.

The F.D.A.’s new focus on implants is a testament to the power of patient activism in the age of social media, as sick women frustrated by their doctors’ lack of answers sought information online, found other patients with similar complaints and banded together to demand regulatory action. One Facebook group has nearly 70,000 members, according to its founder, Nicole Daruda, a Vancouver Island woman who felt well when she got implants in 2005 for reconstruction after cancer surgery, but soon became so ill she had to stop working.

Ms. Daruda had them removed in 2013, and said most, but not all, of her symptoms have lessened.

Another patient activist, Jamee Cook, now 41, had implant surgery for cosmetic reasons when she was 21. Over the next few years she developed so many health problems, including fatigue, memory lapses, migraines and numbness in her hands, that she had to quit her job as a paramedic.

After having the implants removed in 2015, she said, her health has improved. Though she still has some bad days, Ms. Cook said, “It’s been like a 180.”

Silicone-filled breast implants were first marketed in the United States in the 1960s. Over the next few decades, reports of illness emerged. In 1992, silicone implants were banned, except for reconstruction after mastectomy or to replace a previous implant, and then only in clinical trials.

A flood of lawsuits followed.

Studies conducted afterward generally found no link to connective tissue disease, but a few did suggest a connection. In 1999, the Institute of Medicine, then part of the National Academy of Sciences, concluded that overall, there was no evidence that breast implants caused connective tissue disease, cancer, immune disorders or other ailments.

In 2006, silicone implants came back on the market. But manufacturers were required to follow large numbers of women for seven to 10 years, as a condition for F.D.A. approval. Deficiencies in the studies have now prompted the agency to send warning letters to two of the four companies approved to market breast implants in the United States.

One warning letter, sent to the manufacturer Sientra, of Santa Barbara, Calif. on Tuesday, said the company had not kept enough patients in its study of an implant approved in 2012, and warned that if the follow-up monitoring did not improve, the agency could withdraw approval of the implant, effectively taking it off the market.

Rosalyn d’Incelli, vice president of clinical and medical affairs for Sientra, said the company tries to retain patients in follow-up studies by compensating them, contacting them several times a year through email, phone calls, letters and postcards, and transferring them to doctors in more convenient locations. But she said that patients’ work obligations, child care, lack of transportation and other issues often present obstacles.

“We are aware of and take this matter seriously,” Ms. D’Incelli said, adding that the company will respond to the F.D.A. about corrective measures it plans to take. “Patient safety, ensuring long-term safety and effectiveness of our devices and complying with F.D.A.’s requirements are our highest priority.”

Its stock price dropped a little more than four percent on the F.D.A. news.

Last September, the Securities and Exchange Commission accused its former chief executive, Hani Zeini, of concealing damaging information about the manufacturer of its implants before closing a $ 60 million stock offering in 2015. The Brazilian manufacturer had had a certificate of compliance required for selling in the European Union suspended. Sientra said its issue with the S.E.C. had been resolved.

The other letter went to Mentor Worldwide, owned by Johnson & Johnson and based in Irvine, Calif. The F.D.A. said the company had not enrolled enough patients in a study of its MemoryShape implant, approved in 2013, and also threatened to rescind approval for the product. Withdrawing approval for a medical device is time-consuming and rarely occurs.

Mindy Tinsley, a spokeswoman for Mentor, said the company was disappointed by the F.D.A.’s decision to issue a warning letter “despite our good faith efforts to address post-approval study requirements.” She said Mentor notified the FDA last year that it would fall short of study enrollment targets because of changes in consumer preferences, but did not hear back. J&J’s stock remained unaffected on Tuesday.

According to the F.D.A., the other two manufacturers whose breast implants are approved in the United States are Allergan and Ideal Implant, which did not receive warning letters on Tuesday. But their implants have also drawn some illness-related complaints from women.

Plastic surgeons and implant manufacturers often say breast implants are the most intensely studied of all medical devices. But critics and patient advocates say most studies done to date are flawed.

“When plastic surgeons tell women that ‘this is the most studied medical device in the world,’ women assume that means they are proven safe,” said Diana Zuckerman, president of the National Center for Health Research in Washington, D.C., who has been advising advocates for patients with implant-related illness. But, “we still don’t know what percentage of women become seriously ill from their breast implants. We still don’t know why some women get sick right away, some get sick years later and some never get sick.”

Dr. Zuckerman, trained in psychology and epidemiology, will speak at the F.D.A. meeting next week. She wrote a 40-page analysis of breast implant studies, and found that most had not tracked long-term outcomes, or had lost too many participants. In addition, she said, the studies focused only on diseases with specific diagnoses, while ignoring symptoms like joint pain and chronic fatigue. And they were generally too small to detect rare diseases, and were funded by implant manufacturers or plastic surgery associations that had a stake in the outcomes.

Newer studies looking at long-term outcomes have found disproportionately high rates of some uncommon chronic diseases among women with implants, though these studies show only associations and do not prove a cause-and-effect relationship.

Plastic surgeons at M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston who looked at the long term outcomes of 99,993 women with silicone implants reported finding they had six, seven and eight times the normal population rates of rheumatoid arthritis, scleroderma (a connective tissue disease) and Sjogren syndrome (an autoimmune disorder), all of which are relatively rare diseases.

An author of the study, Dr. Mark Clemens, cautioned that it did not prove cause and effect, and said in an interview, “The overarching message is that breast implants are reasonably safe and have high patient satisfaction, but also have complications that patients should be made aware of.”

Critics said the study, published in Annals of Surgery in September, did not adjust for underlying differences between women with and without implants, and that the data, drawn from the F.D.A.’s own database, was flawed because of high dropout rates.

“All the evidence we have to date is that implants are safe,” said Dr. Amy S. Colwell, a plastic surgeon at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston who wrote an editorial criticizing the study, and who is a consultant for Allergan, an implant manufacturer.

An Israeli study published in December that was based on a health insurer’s medical records, compared 24,651 women with silicone breast implants to 98,602 similar women without implants, and found that those with implants had a 22 percent increase in the risk of having any auto-immune or rheumatic disorder. It also found higher rates of Sjogrens, scleroderma and rheumatoid arthritis, as well as other illnesses.

“Implants are not so innocent as presented,” said Dr. Howard Amital, a rheumatologist who was the study’s senior author. Though he acknowledged the study does not prove a causal relationship, he said that the association between implants and the disorders “is highly indicative.”

“There is a reason for concern,” he added. “There is something we cannot ignore.”