Although it is widely accepted that perimenopausal women are at increased risk for depressive symptoms, little research exploring suicidality in mid-life women has been conducted. In the spirit of Suicide Prevention Month, we will review here the risk of suicidality in midlife women and what factors may be at play in modulating this risk.

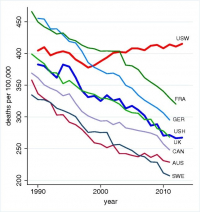

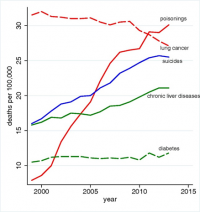

Prior to 1999, the United States experienced a steadily declining rate of mortality for midlife adults, a trend consistent with other industrialized/western countries. However, beginning in 1999, this trend was reversed in the United States alone and all-cause mortality rates in the US began to rise (Figure 1, below). Among other causes of death (Figure 2, below), deaths by suicide were one of the driving forces in this increase in mortality (Case and Deaton, 2015).

“Fig 1: All-cause mortality, ages 45–54 for US White non-Hispanics (USW), US Hispanics (USH), and six comparison countries: France (FRA), Germany (GER), the United Kingdom (UK), Canada (CAN), Australia (AUS), and Sweden (SWE) (Case and Deaton, 2015). “Fig. 2 presents the three causes of death that account for the mortality reversal among white non-Hispanics, namely suicide, drug and alcohol poisoning (accidental and intent undetermined), and chronic liver diseases and cirrhosis. All three increased year-on-year after 1998 (Case and Deaton, 2015).”

To examine the increase in deaths by suicide, Hu and colleagues used the Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS) to investigate suicidality in different populations from 1999 to 2005. The overall rate of suicidality during this time increased by 0 .7% for Americans across age and ethnic groups. However, this increase was not evenly distributed among subgroups. In fact, midlife adults were the primary force behind this increase in deaths by suicide. They found that the cohort of White, non-Hispanic adults aged 40-64 had a 3% annual increase in deaths by suicide during this time period. Within this cohort, men had an annual increase of 2.7% of deaths by suicide and women had an annual increase of 3.0%. Notably, for other racial and ethnic groups in midlife, there was no increase in suicidality during this period (Hu et al., 2008). These startling results beg the question: Why are midlife adults now at increased risk for death by suicide?

In a comprehensive review by Case and Deaton (2015), midlife adults have an increased risk of “deaths of despair”. In their large self-report survey, they found that participants in this age group reported a significant decline in overall health, including declines in mental health, increases in reports of chronic pain, declines in the ability to perform daily activities, and worsening liver functioning. When asked about the status of their health over the period from 1999 to 2013, 6.7% fewer participants annually reported having excellent or very good health. Further, the percentage of midlife adults with serious mental illness rose from 3.9% to 4.8% between 1997 and 2013 – adding an additional day per month on average of days that the participants reported that their mental health was not good (Case and Deaton, 2015).

While declines in physical and mental health are interlinked and may help explain an increase in suicidality in midlife adults generally, there is still little research on why midlife women are particularly at risk. Indeed, a 2009 study of European women found that women in the perimenopausal period were at an almost 7-fold increased risk of suicidal ideation compared to women in the pre or post-menopausal period or men in any age group. Perhaps most strikingly, this study found that suicidal ideation in perimenopausal women increased compared to their counterparts independent of underlying mood disorders. This is to say, while women and men with underlying mood disorders were more likely to have increased suicidal ideation, women without underlying mood disorders still experienced an increase in suicidal ideation during the perimenopausal period (Usall et al., 2009).

Several studies examining the association between hormonal fluctuations across the menstrual cycle and suicidality may provide a starting point in explaining these findings. A 2006 literature review examined rates of attempted suicide and death by suicide over the menstrual cycle to uncover associations between suicidality and hormone fluctuations. While they did not find that deaths by suicide were associated with any particular phase of the menstrual cycle, they did find that there was some evidence to suggest that suicide attempts were associated with both the first week of the menstrual cycle and premenstrual symptoms (Saunders and Hawton, 2006). In their conclusion, the authors speculate that the increase in suicidality during those periods may be linked to periods of low estrogen or the fluctuation of ovarian steroid hormones. Importantly, menopausal and perimenopausal women were excluded from this study and there is still a paucity of research investigating how hormonal fluctuations affected suicidality specifically in midlife women, who experience more dramatic hormonal fluctuations as they transition to menopause. A recent study, covered extensively in a previous blog, found that “increasing dysregulation of ovarian hormones, but not VMS [vasomotor symptoms], was associated with more depressive symptom burden during the menopausal transition” (Joffe et al., 2020). It is important to note here that suicidality and depressive/mood symptoms do not always occur in tandem.

Therefore, it seems that a decline in overall health, race/ethnicity and geography, and hormonal fluctuations during this time period may all play some role in the increasing risk of suicidality for midlife women. Further research in this area is desperately needed to examine this at-risk population and create intervention and treatment strategies.

Phoebe Caplin, BA

Case, A., & Deaton, A. (2015). Rising morbidity and mortality in midlife among white non-Hispanic Americans in the 21st century. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(49), 15078-15083.

Hu, G., Wilcox, H. C., Wissow, L., & Baker, S. P. (2008). Mid-life suicide: an increasing problem in US Whites, 1999–2005. American journal of preventive medicine, 35(6), 589-593.

Joffe H, de Wit A, Coborn J, Crawford S, Freeman M, Wiley A, Athappilly G, Kim S, Sullivan KA, Cohen LS, Hall JE. Impact of Estradiol Variability and Progesterone on Mood in Perimenopausal Women With Depressive Symptoms. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020 Mar 1; 105(3):e642-50.

Saunders, K. E., & Hawton, K. (2006). Suicidal behaviour and the menstrual cycle. Psychological medicine, 36(7), 901-912.

Usall, J., Pinto-Meza, A., Fernández, A., de Graaf, R., Demyttenaere, K., Alonso, J., … & Haro, J. M. (2009). Suicide ideation across reproductive life cycle of women Results from a European epidemiological study. Journal of affective disorders, 116(1-2), 144-147.