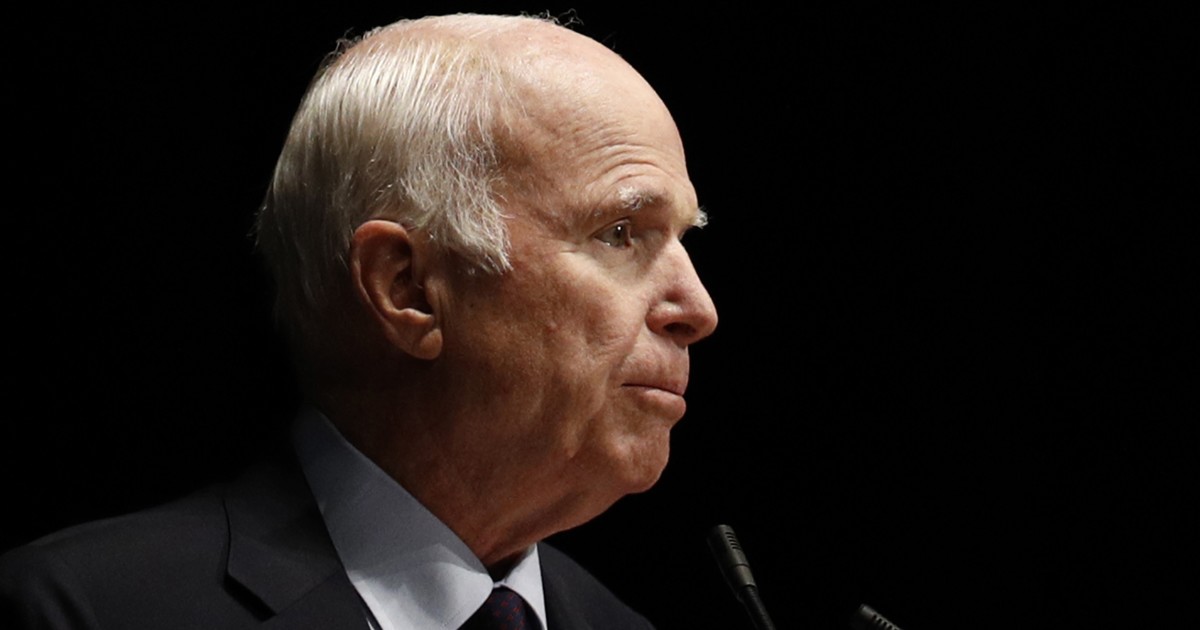

Rep. Jason Lewis, R-Minn., who narrowly lost his suburban House district south of the Twin Cities last Tuesday, wrote in the Wall Street Journal on Sunday that the late Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz., killed the GOP House majority when he voted down the “skinny” Obamacare repeal bill last July.

Instead of getting conspicuously offended by this, which seems popular, I thought it might be worth looking at how much truth there is to it.

Lewis wrote:

The basic argument is that because this bill failed to pass, Democrats (and a pro-Democratic media) were freer to demagogue its provisions and act like everyone was going to lose their coverage, when in fact it was untrue or at least highly unlikely. Because no one was actually experiencing life under the AHCA after it failed, they could claim that each Republican House member’s vote was a vote to make the sky fall. And it worked — or so goes the argument. This might sound familiar if you’ve been following the Obamacare debate long enough — if you don’t pass the bill, you don’t find out what’s in it. Or rather, what’s not in it.

That’s how healthcare surprisingly became the Democrats’ go-to issue in the midterm elections, not just in the House but also in Senate contests in Florida, Montana, and Missouri, among others. Lewis admits that all Republicans deserve some blame: “[I]nstead of running away from health-care reform after it failed, Republicans should have leaned in on the plan’s most important aspects. But because the AHCA didn’t pass, it was impossible to refute the lies about it.”

Is this really true? First of all, it assumes that the “skinny” plan would have worked without causing even more backlash than there was. As then-Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi learned in 2010, when you pass a bill, you own it. And as former President Barack Obama learned in 2014, when you implement a bill, you also own it.

Second, accepting arguendo that failure to pass AHCA was a net negative for the GOP, Lewis’ argument forces us to assume that the political benefits of passing the AHCA would have been great enough not only to improve Republicans’ performance, but to do so by enough that they might have won perhaps as many as 20 of the House seats they appear to have lost.

About that, I’m not so sure. House seats get lost and won for all kinds of reasons. Lewis’ own seat, I’m pretty sure, did not have to be lost, but his opponent and the national media seized on his own baggage from his career as a former radio host. Lewis was already a controversial figure when he ran in 2016, whom most forecasters didn’t expect to win. He did win, but now he’s lost for the same reasons people didn’t think he’d win in the first place. (I’m guessing this is one of the seats Republicans will win back next time, especially if President Trump targets Minnesota, which he most certainly will.)

That aside, I understand the argument Lewis is making. And I’m still pretty skeptical. Given the increasingly powerful rebuke of the sitting president that we’ve seen in each of the last three midterm elections (2006, 2010, 2014), I’ve come to believe that this is a feature of our current hyper-partisan political landscape. Election 2018 was actually a pretty mild rebuke in comparison not only to those other midterms, but also to what I think most people have been expecting all year — especially what they were expecting back before the confirmation of Justice Brett Kavanaugh. It was certainly mild compared to what I was expecting.

And even if you disagree with me there, let’s think for a moment about the “skinny” Obamacare repeal bill itself. Like our own Philip Klein, who knows a lot more about the issue than I do, I viewed it as Republicans’ last-ditch effort to be able to say they did something, not necessarily an effort to do much of substance. Yes, maybe it would have helped the party rhetorically on the campaign trail, but it was a gimmick that Klein wrote ” wouldn’t repeal much of anything,” and left 411 out of Obamacare’s 419 sections intact.

If healthcare really was the final nail in the coffin of the GOP House majority — and I’m not even convinced of that because I think the election was mostly a referendum on Trump in the states and districts where it was closely fought — then blame the Republicans for failing to reach consensus on healthcare. Blame the conservatives and blame the moderates for failing to compromise and reach an acceptable solution.

Republicans were more than happy to ride the wave in 2010 and 2014 when Obamacare’s toxicity was boosting Republican fortunes. But they never had a clue about how to unwind the new law they campaigned so harshly against, and it would be a mistake to pin that on John McCain.