One of Irena Romeo’s earliest memories is arriving at Newcastle Harbour’s Lee Wharf as a three-year-old.

“I remember the thousands of bags. They were all brown, all the same. As a little girl it felt like an eternity, looking for the luggage – walking up and down.

“You know, my mother’s luggage didn’t arrive. All that was precious to her, she lost.”

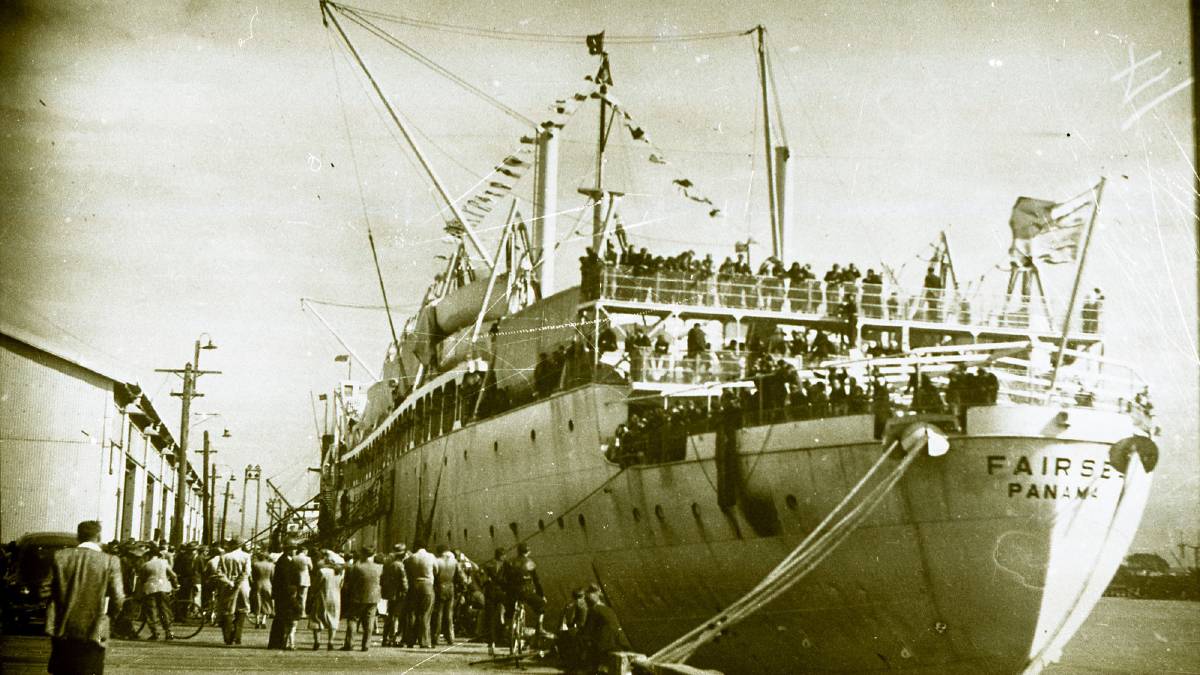

Ms Romeo, a Dudley resident and former principal of three local primary schools, was one of the almost 2000 displaced persons who arrived in Newcastle on August 19,1949, aboard the Fairsea.

The vessel was the first migrant ship to come to the city. Monday will mark the anniversary of its arrival 70 years ago.

ARRIVAL: The Fairsea docked at Newcastle Harbour on August 19, 1949. Picture: University of Newcastle’s cultural collections.

Ms Romeo travelled from Naples to Newcastle on the ship with her parents Roman and Bronia Hromyk.

Originally from Poland, Ms Romeo’s parents had been enslaved by the Nazis at the beginning of World War II and taken to Bavaria. Before boarding the Fairsea, the family had lived in a United Nations-run migrant camp. This was where Ms Romeo was born.

For Newcastle, the Fairsea represented the beginnings of a multicultural future.

For its passengers – people unable to return to their homelands of Poland, Hungary, Ukraine, Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia and other Baltic States – the ship carried the hope of belonging somewhere entirely unknown.

“The ship gave all these people who had suffered so many hardships an opportunity for a new life, a new beginning and freedom,” Ms Romeo said.

The journey of Ms Romeo’s parents began when her mother was taken from her family’s farm at 13 years of age.

“She was forcefully abducted and deported to Germany as slave labor. They were packed into cattle trains, the conditions on board were horrendous,” she said.

“When they arrived the men and women were separated. They had to strip and they were hosed down. Then the German people chose who they wanted to work for them.”

Ms Romeo said her mother was “very lucky” to be picked by a woman who was “very kind and good to her”. She worked on a farm during the day, and in her hausfrau’s tavern at night – where she once saw Hitler.

During this period, Bronia met her future husband, Roman Hromyk, another Pole who had been forced to work in an ammunition factory nearby.

DEPART: Irena Romeo, 3, with her parents Roman and Bronia Hromyk, left, her French Godparents, right, before boarding the Fairsea.

“He was very unlucky, not like my mum,” Ms Romeo said.

“He was treated really badly. My mother said he was very thin.

“He was a first-year law student, 18-years-old, when he was rounded up by the Nazis – he and his best friend. They tried to escape and his friend was shot dead in front of him.”

Ms Romeo said her mother would keep her rations and take them to Roman in secret.

“She saved her own food and would sneak it to Dad in her coat,” Ms Romeo said.

At the end of the war millions of forced laborers from Poland and other conquered territories were freed by the Allies. Ms Romeo’s parents were taken to a huge camp for displaced persons run by the United States and later the United Nations.

“They were told that their homeland had been bombarded and was under communist rule.

“The camp itself was a temporary home for 20,000 people, most of whom were Polish. There was a lack of food, a lack of clothing, medicine and indescribable poverty.”

The pair married at Camp Wildflecken and it’s where Ms Romeo was born.

“They were in the camp for four years,” Ms Romeo said.

“My father would collect the cigarette rations he was given and exchange it with the dairy farmers nearby in order to get milk for me.

“The children of six of my parents’ friends died at the camp.”

In 1947 the International Refugee Organisation took over Wildflecken and began re-homing its residents. Newcastle’s offer of permanent residency and two years of guaranteed work was very attractive to the family.

The family travelled from Germany to board the Fairsea in Naples in July, 1949. It was the ship’s second voyage from Europe to Australia since it was converted from an aircraft and trooper carrier at the end of the war.

Ms Romeo said she did not have many memories from the journey, except falling down stairs while trying to visit her father on the deck below.

“There was no cabins. Just a huge open space. The bunks were tripled and the men were separated from the women and children.”

Newspaper articles from the day of the ship’s arrival in Newcastle demonstrate a deep curiosity about its 1,896 passengers. One article assured readers the new arrivals looked “healthy and well”. “Most of them were cheerful and smiling.”

Another documented the diversity of people on board. “There’s several doctors, several lawyers, a Hungarian professor … and a Hungarian countess,” it said. There was an Olympic weightlifter and champion swimmer to boot.

Irena Romoe and her mother at Fly Point.

Ms Romeo’s family only stayed at the camp for three months before being transferred to a smaller camp at Fly Point at Nelson Bay.

It was at Nelson Bay the family made many lifelong friends and long-lasting memories. Ms Romeo’s sister Ursula was born at the camp in 1951.

Roman was bused in and out of the BHP steelworks each day where he worked in the coke ovens.

“We thought it was paradise,” Ms Romeo said. “They had a teacher that took us on bush walks in the afternoon, we’d go fishing and everyone seemed to get on well. We loved it.”

After two years the family saved up enough to move out of the camp and build a house on the “cheapest piece of land possible” – in Argenton.

“Dad watched how the builders of the housing commission pitched their roofs and he built the house, and helped three of his friends build their houses. My father, who had been studying to be a lawyer.”

Roman continued working at BHP and Bronia became a “champion presser” at Rundles tailoring. They got used to being called “Berryl” and “Jack” by their Australian neighbours.

Irena Romeo as a baby.

Ms Romeo’s family were part of a very tight-knit community of migrants and would meet regularly with other families from the Fly Point camp.

“We would have a feast all afternoon and sing together,” Ms Romeo said.

“Every weekend we would go to Anzac House, which would alternate between hosting Polish, Italian, Ukrainian, and Yugoslavian dances. We’d go to all of them.

“We brought this new attitude of multiculturalism with us.”

Ms Romeo said school was not easy. She had to learn English and was teased by other children for her strange name.

In year two, however, she received her first ever book.

She won “Johnny Appleseed” for coming third in the class. She has been passionate about learning ever since.

“The most important thing to my parents was a good education,” she said. “My mum said that in Australia you could be whoever you wanted to be.”

Ms Romeo became a teacher and went on to serve as the principal at St Joseph’s Primary School in Merewether, St Therese’s in New Lambton and St John Vianney in Morisset.

“I loved working and I love children. I very rarely took time off. It was this work ethic my parents gave me. They worked so hard.”

On Sunday, Ms Romeo will attend the celebration of the 70th anniversary of the Fairsea’s arrival, taking place at Newcastle’s Ukrainian Catholic Church.

Many of the church’s parishioners are direct descendants of migrants who arrived on the Fairsea, including Tanya McPhee, who will be the master of ceremonies for the mass and luncheon.

Ms McPhee’s mother Olga Bazalej, née Tarnawskyj, was also three-years-old when she arrived in Newcastle.

The anniversary of the ship’s arrival coincides with the 28th anniversary of Ukrainian independence and the annual religious tradition “the blessing of the fruit”.

Ms McPhee said her mother had been cooking all week in preparation for Sunday.

“It’s so emotional,” Ms McPhee said. “Me and my children, we continue the Ukrainian culture so that there will always be that reminder of where we came from and how we got here.”

Bronia and Roman Hromyk passed away at the age of 59 and 71 respectively.

Ms Romeo is now the grandmother of four “beautiful” grandchildren.

She will spend Monday with her four close friends who also traveled on the Fairsea.

“We will get together and reminisce.”