In this, our final week of daily publishing as we wind down operations due to a loss of sufficient funding, I want to share some observations after a 45-year career in health care journalism, 13 of which were the pinnacle for me as Publisher of this website.

Earlier this year, after Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s “surprise” primary election victory that perhaps shouldn’t have been a surprise, the Washington Post’s media columnist wrote:

“(Journalists) need to get closer to what voters are thinking and feeling: their anger and resentment, their disenfranchisement from the centers of power, their pocketbook concerns.”

More recently, a Columbia Journalism Review article on media diversity issues focused on an urban crime story in The New York Times. An excerpt:

“The story, to me, spoke to the problem of what happens when the demographics of the Times—and American newspapers in general—look nothing like the demographics of the communities they cover. The people who are most likely to appear in these kinds of stories are the least likely to have a say in how those stories are told.”

The same critique could be made – but rarely is – about health care news.

Too few health care journalists know their readers’ needs

There is a Grand Canyon-sized gap between the kind of information that patients and consumers need and what they’re actually getting in most health care news stories and PR news releases. Most, but not all.

Today, too many people (but, again, not all) writing and reporting on health care are not connected to what their audience is thinking and feeling – their true concerns. In part, it’s because some writers/reporters are tied to their computer screens and the daily drumbeat of dreck that comes to them in PR news releases and industry handouts. Some aren’t given the opportunity to get out and meet patients and health care consumers, or the time to seek out these people online. If they include a patient perspective, it’s often one that is gift-wrapped and spoonfed by a PR person serving up the rosiest, most satisfied and possibly unrepresentative patient story imaginable.

I recently wrote about Medicare open enrollment issues that I don’t see journalism adequately addressing. There aren’t many Medicare-aged journalists any more and there weren’t many Medicare recipients interviewed in the stories I saw. But an estimated 44-million people, 15% of the population, are on Medicare.

Battling health care hype for decades

I started covering health care news in the ‘70s, when there were very few fulltime health care journalists in the US. I had no specialized training for this assignment, but taught myself.

Nixon’s “War on Cancer” drew the publicity the President hoped for, but I was more intrigued by University of Chicago statistician John Bailar’s analysis that “It is difficult to claim success in the war against cancer on the basis of (the evidence).”

In the ’70s, I interviewed Houston’s Dr. Michael Debakey about his artificial heart research. Then in 1984, I reported on the Robert Jarvik/William DeVries artificial heart partnership as it moved from the academic setting at the University of Utah to the corporate Humana hospital environment in Louisville. I had a front row seat to watch the hype surpass the true hope, and to reflect on the insidious influence of corporate pressures.

In the ’70s, I interviewed Houston’s Dr. Michael Debakey about his artificial heart research. Then in 1984, I reported on the Robert Jarvik/William DeVries artificial heart partnership as it moved from the academic setting at the University of Utah to the corporate Humana hospital environment in Louisville. I had a front row seat to watch the hype surpass the true hope, and to reflect on the insidious influence of corporate pressures.

I reported on U.S. Department of Health & Human Services Secretary Margaret Heckler’s 1984 prediction that “We hope to have (an AIDS) vaccine ready for testing in about two years.” How’d that work out?

Also in 1984, I saw my own network, CNN, join in the incredible runaway hype of extremely early Alzheimer’s disease research at Dartmouth. Jay Winsten, who is now director of Harvard School of Public Health’s Center for Health Communication, addressed the episode in a landmark piece in Health Affairs, “Science and the Media: The Boundaries of Truth.” He wrote: “This case illustrates serious issues. Many news organizations have not developed adequate criteria (even informal ones) for evaluating when a science story has achieved a minimal threshold of validity.”

In 1990, I objected when CNN, my employer at the time, reported on a blood-heating experiment in AIDS patients. In Quill, the magazine of the Society of Professional Journalists, I wrote:

“A story was rushed into place in reaction to a local Atlanta television station’s disclosure of this experiment. Strikingly, and in violation of journalistic good judgment, no second opinion was sought before the story aired. Only the statements of the physicians who were carrying out the experiment appeared in the original story.

TIME magazine reviewed the CNN coverage in its ethics column of June 25, 1990: “What is a TV viewer, particularly one who has AIDS, to make of this story? Is the treatment a miracle cure? Or is it a mirage that cruelly raises the hopes of AIDS sufferers?”

Pack journalism set in and many members of the media picked up on the story. The coverage led to such a furor that several federal government researchers visited the hospital where the experiment took place. They reported that the hyperthermia “appeared to have offered no clinical, immunologic or virologic benefits.” … Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, accused the experimenters. He said, in a September 1990 Associated Press story, that they caused “a lot of confusion, frustration and false hope on the part of HIV-infected individuals….This is just another example of why we’ve got to be careful before we jump on claims…of a new treatment or cure.”

I resigned from CNN in disgust not long after.

I shuddered in 1998 when Gina Kolata’s front page story in the Sunday New York Times quoted a senior scientist (from a dinner party conversation) predicting that a researcher would “cure cancer in two years.” That story caused the biggest backlash I’ve ever seen about science journalism. (The quoted researcher later denied saying that.)

The seeding of an idea for HealthNewsReview.org

Those were just a few of the stories that shaped my thinking about what I could do over the rest of my career to try to improve health care journalism and, if not, to improve the critical thinking of patients and consumers in the face of rampant sensationalism.

In 2000, I wrote about “The Seven Words You Shouldn’t Use in Medical News.” The words were: cure, miracle, breakthrough, promising, dramatic, hope, victim. The words were not mine. All were suggested to me by patients I had interviewed through the years.

A researcher even older than me recently sent me recommendations for what I should add to my 2000 list:

Innovative

Definitive

Original

Unique

Groundbreaking

Leading- or cutting-edge

State-of-the-art

Pioneering

Successful

Novel

The themes overlap and coincide. The words matter. The evidence matters. Conflicts of interest matter. Helping patients and the general public cut through hype matters. This became the blueprint for the latter half of my career.

I always try to credit a pioneering effort named Media Doctor Australia, launched by researchers Amanda Wilson and David Henry and colleagues, as the model for HealthNewsReview.org. They allowed me to adopt their review criteria, which became the systematic backbone of our efforts. Then Floyd J. “Jack” Fowler, PhD, president of the Foundation for Informed Medical Decision Making (now defunct), convinced his board of directors to fund my fledgling project in 2005. I never thought we’d last this long. We had created a monster. The last four years of funding, from the Laura and John Arnold Foundation, helped us develop the project into the leading voice of its kind in the world.

I always try to credit a pioneering effort named Media Doctor Australia, launched by researchers Amanda Wilson and David Henry and colleagues, as the model for HealthNewsReview.org. They allowed me to adopt their review criteria, which became the systematic backbone of our efforts. Then Floyd J. “Jack” Fowler, PhD, president of the Foundation for Informed Medical Decision Making (now defunct), convinced his board of directors to fund my fledgling project in 2005. I never thought we’d last this long. We had created a monster. The last four years of funding, from the Laura and John Arnold Foundation, helped us develop the project into the leading voice of its kind in the world.

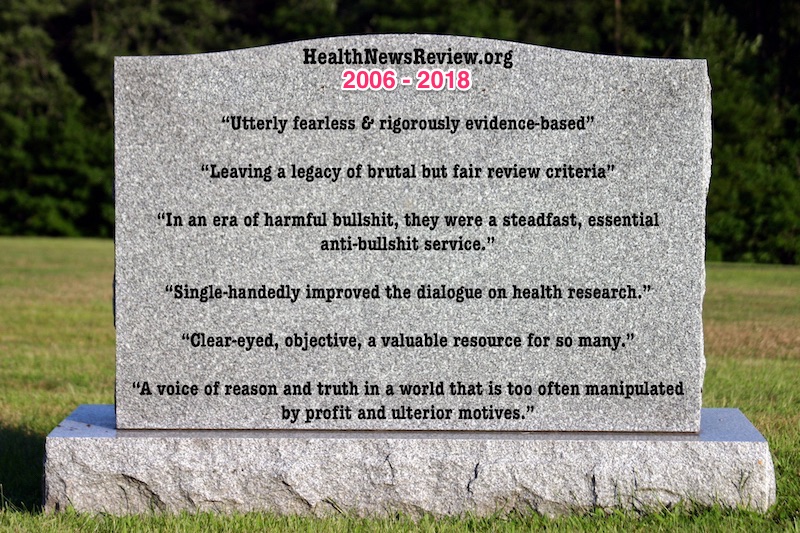

What people have said about HealthNewsReview.org

This graphic captures some of the most thoughtful things that our followers wrote about us. It’s on a headstone because I would love it if that’s the way we would be remembered.

Rarely, we also got ugly Twitter messages from a journalist, such as:

“I thought HealthNewsReview died from lack of interest. Oh, well, soon enough thankfully.”

Another journalist Tweeted in response to that ugliness:

“Perhaps those who rolled their eyes at the site’s reviews weren’t really engaged with feedback – from HealthNewsReview.org or anyone else.”

Far more often, journalists expressed their appreciation for our efforts.

From a veteran health care journalist:

“Thanks very much. Your reviews help make the case when editors sometimes think certain details or numbers are expendable.”

One of my clearest reflections after 13 years of work on this project is how much I admire the journalists who are open-minded and accepting of constructive criticism. Conversely, I have always felt pity for the journalists who are thin-skinned and defensive about any and all such constructive criticism. Whose interests are they serving?

But whatever the response was from journalists, and regardless of the accolades and awards that this project has garnered, it is the feedback from patients and consumers that has been most heart-warming. They told us that they were getting help from us that they couldn’t get anywhere else. Examples:

“Thank you for this helpful counterweight to the breathless and lazy coverage of (this drug) by most mainstream outlets,” patient response to our article on a new ALS drug.

“So often HealthNewsReview pinpoints problems with news stories that patients could never glean themselves. I’m thankful to have the HNR watchdogs on the trail of truth!” – from patient advocate Trisha Torrey.

“Thank you for your most important ‘call out’ to hype related to trials and outcomes in Alzheimer’s & related dementia treatments. I concur this is inauthentic and cruel to families. Shame on the media for such distortion.” – patient response to our critique of ” ‘Historic breakthrough Alzheimer patients around the globe have been awaiting’ “

“Too often the health stories we read have been poorly analyzed and reported on by today”s time-pressured reporters. The reviews and methodology presented on this site can help patients bring better quality information to the care relationship with their clinicians, and help all parties make better informed decisions.” – from leading patient advocate “e-patient Dave” DeBronkart.

There’s no way I can capture all of the kind words from patients, health care consumers and others who relied on our public service project to help them navigate the confusion of American health care. There’s no way that I can thank them adequately for their interest and support. I’ve written personal thank you notes to nearly 400 individuals who have made donations to our project to keep us going. I can’t tell you how moved I am by their thoughtfulness and generosity.

A long strange trip

As I have grown older, some people have told me that I look a little like the Grateful Dead’s Jerry Garcia. I don’t know. I do know that I love what Jerry said about protecting the rain forests:

As I have grown older, some people have told me that I look a little like the Grateful Dead’s Jerry Garcia. I don’t know. I do know that I love what Jerry said about protecting the rain forests:

“Somebody has to do something, and it’s just incredibly pathetic that it has to be us.”

Well, it won’t be us any longer working every day to help people improve their critical thinking about health care. At least not nearly as often nor, perhaps, as forcefully or with as much impact as I slip into at least semi-retirement. But I am incredibly thankful for the opportunities I’ve had and for the wonderful people who have worked with me on this project over the last 13 years.

I have written elsewhere about some of the news and information sources that people could turn to in our absence. They – and others – are doing important, innovative work. Many of these journalists have changed and adapted to changing times.

Garcia famously said about his music, “To me, being alive means to continue to change, never to be where I was before.”

And so change has come for me, my team, and HealthNewsReview.org. This band is breaking up. Even at this 11th hour, people continue to suggest that somebody someday will pick up the baton again.

What a long, strange and gratifying trip it’s been. Thanks for coming along for the ride.