‘Long Covid’ IS real: Three-quarters of coronavirus patients who were admitted to hospital still suffer symptoms THREE MONTHS later, study reveals

- Researchers studied 110 patients admitted to Southmead Hospital in Bristol

- A total of 81 said they were still experiencing at least one symptom on follow-up

- Many were also suffering from poor quality of life and struggled with daily tasks

Almost three quarters of Covid-19 patients admitted to hospital still suffer symptoms three months later, a study has claimed.

Researchers found that 81 out of 110 patients had breathlessness, fatigue and muscle aches long after their battle with the disease.

Many also struggled to carry out daily tasks such as washing, dressing or going back to work because of their ‘long Covid’, scientists claimed.

Doctors at Southmead Hospital in Bristol found one in seven survivors had evidence of lung scarring in abnormal chest scans.

Matt Hancock has already admitted that he is ‘worried’ about the long term impacts plaguing coronavirus ‘long-haulers’.

The Government has pumped £10million into studies into the long-lasting effects of the disease, which some experts have called ‘this generation’s polio’.

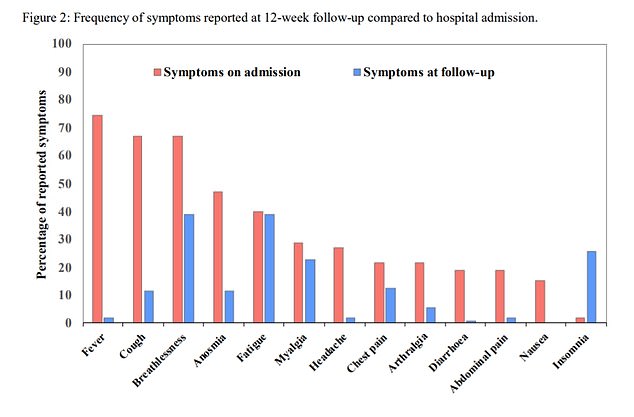

This graph shows how many patients reported each symptom when they were admitted to hospital and 12 weeks later. It shows the initial symptoms of a fever, cough and loss of taste/smell have reduced. But breathlessness, excessive fatigue and muscle aches have persisted

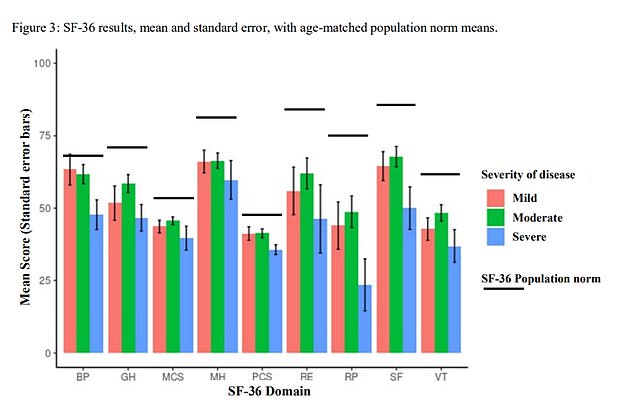

The graph shows how the health life quality scores of Covid-19 hospital patients (mild, moderate and severe) were lower than those of the population (black lines)

The new findings are from the North Bristol NHS Trust’s Discover project, which is studying the longer-term effects of coronavirus.

Dr Rebecca Smith, study co-author, said: ‘There’s still so much we don’t know about the long-term effects of coronavirus.

‘But this study has given us vital new insight into what challenges patients may face in their recovery and will help us prepare for those needs.

‘We’re pleased researchers at Southmead Hospital are leading the way and hope our findings can help patients and their GPs understand the course of post-Covid illness and the role of routine tests.’

A total of 163 patients with coronavirus were recruited to the study. Nineteen of those died.

The remainder were invited for a three-month check-up and 110 attended.

The majority of patients (65) had needed oxygen when they were hospitalised. Some 27 did not need oxygen therapy, while 18 were treated in ICU.

Most (74 per cent) had at least one persistent symptom — notably breathlessness and excessive fatigue, which were both reported by 39 per cent of volunteers.

Insomnia was reported by 24 per cent of patients. Fewer than five per cent of the volunteers said they were struggling to sleep when they were admitted to hospital.

Patients who had suffered more severe Covid-19 reported more symptoms on their follow-up.

Only patients who required oxygen therapy in hospital had abnormal radiology, clinical examination or lung function.

Of the 110 patients, 15 patients had abnormal radiographs, which suggest lung scarring. Two patients’ readings had worsened since they were allowed home from hospital.

When looking at their quality of life, respondents with lasting symptoms scored lower. Again, those who had more severe Covid-19 were affected worse.

Patients had been asked to fill out the SF-36 questionnaire to get a score between zero and 100, with higher scores indicating better health quality of life.

It measured general perception of health, energy, body pain and feeling limited in daily tasks due to either physical or emotional problems.

The researchers did not give a figure for how much worse Covid-19 survivors’ scores were compared to the general population.

But a bar chart of the findings show Covid-19 patients scored lower in every aspect.

For example, those who had been hospitalised but not given oxygen therapy scored their energy at around 40, compared to 62 in the general population.

The preliminary findings were published on August 14 as a pre-print paper, meaning they have not been looked at by other academics.

The research is due to continue at Southmead Hospital, with researchers collaborating with the University of Bristol to look at blood test results, rehabilitation therapies and psychological support.

Dr David Arnold, who is leading the Discover project, said: ‘This research helps to describe what many coronavirus patients have been telling us: they are still breathless, tired, and not sleeping well months after admission.

‘Reassuringly, however, abnormalities on X-rays and breathing tests are rare in this group. Further work in the Discover project will help us to understand why this is, and how we can help coronavirus sufferers.’

Although this study found persistent symptoms were typically higher in those who were more severely ill, ‘Long Covid’ has been anecdotally reported by people who only had mild cases of the disease that they expected to be over within a week.

Early this month, MPs from the All Party Parliamentary Group on coronavirus heard from previously fit people whose lives have been turned upside down by a host of symptoms.

Claire Hastie, who is a member of a Long Covid Support Group on Facebook, described how she used to cycle 13 miles to work but can no longer walk 13 metres and is now largely confined to a wheelchair with her children providing much of her care.

Dr Jake Suett, a staff grade doctor in anaesthetics and intensive care medicine, said: ‘I was doing 12-hour shifts in ICU.

‘And now a flight of stairs or the food shop is about what I can manage before I have to stop… if I’m on my feet then shortness of breath comes back, chest pain comes back.’